Boston Parks Celebrates Black History Month 2026

We're honoring Black History Month this year by giving a spotlight to some of the stories behind Boston's neighborhood spaces and the people who not only impacted our wonderful home, but also are recognized within our parks. Commemorate their legacies by visiting Boston’s public spaces with a stronger understanding of their struggles and achievements.

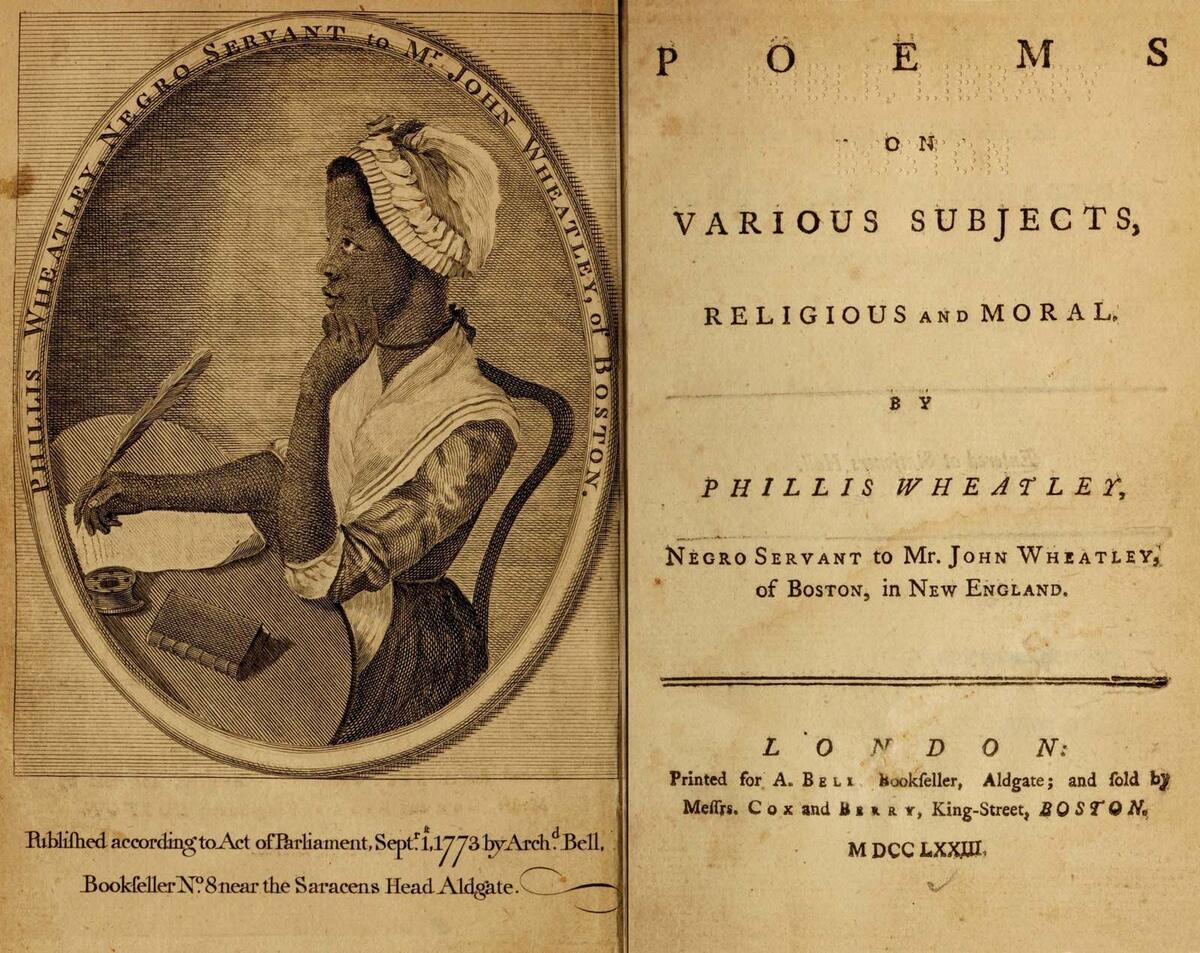

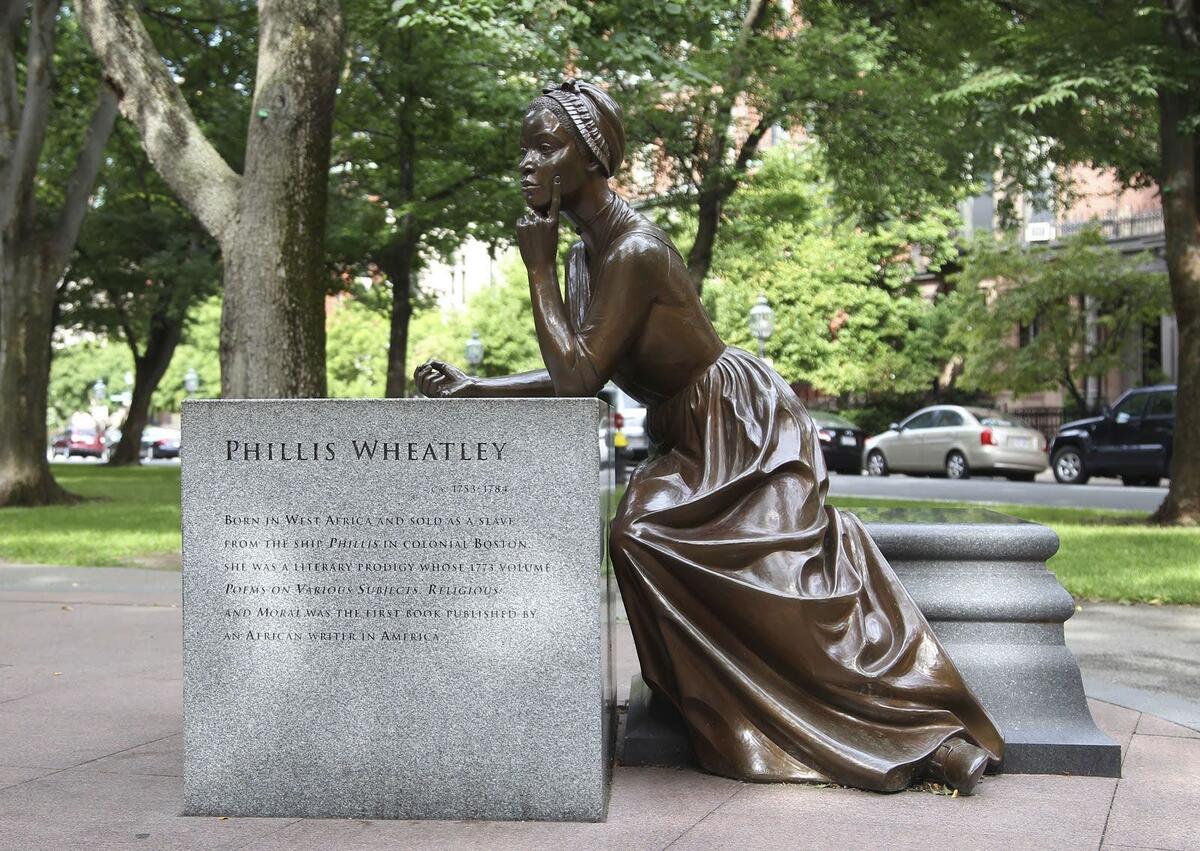

Phillis Wheatley

Commonwealth Avenue Mall, Back Bay

- If you’ve ever stood between Fairfield Street and Gloucester street at Back Bay’s Commonwealth Avenue Mall, you have likely seen The Women’s Memorial. This series of statues, created by Meredith Bergmann, portrays three important women who have deep-rooted connections to Boston, including Abigail Adams, Lucy Stone, and Phillis Wheatley. To dive more into one of these figures, let’s learn a little more about an internationally acclaimed woman, and the United States’ first published African American poet: Phillis Wheatley.

- In 1761, at just seven years old, Phillis Wheatley was taken from West Africa and forced into slavery in Boston, Massachusetts, where she would be purchased by John Wheatley as a servant for his wife. After the strenuous journey across the ocean, young Phillis was frail and unhealthy. In the time she took to build strength, her enslavers saw an undeniable intelligence in her. The Wheatley’s elected to teach her to read and write during this time. Despite grim beginnings, she would emerge as a literary prodigy.

- Wheatley published her first poem, inspired by famous English poets like John Milton and Alexander Pope, at age thirteen. Six years later as a nineteen year old, she released a book titled: Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, which gained international recognition and addressed themes of race, spirituality, patriotism, and redemption. She would go on to travel internationally with her enslavers, where she was warmly received and given celebrity treatment.

- Phillis Wheatley was freed from slavery at the very start of 1774 just before the death of Mrs. Wheatley. She later married, having children and becoming Phillis Wheatley Peters. Up until her death in 1784, which was likely brought on by health struggles related to living in poverty, Wheatley never put down her pen. She continued to write poetry, publishing singular poems and attempting to create a second volume of her poems and letters. Her final manuscript, which was thought to have around 145 poems, has since been lost.

- Phillis Wheatley will forever be remembered as the first African American and first enslaved person in the U.S. to publish a book of poems, as well as the third American woman ever to be published.

- Read more about Phillis Wheatley and The Women’s Memorial at the Commonwealth Avenue Mall.

Photos from britannica.com

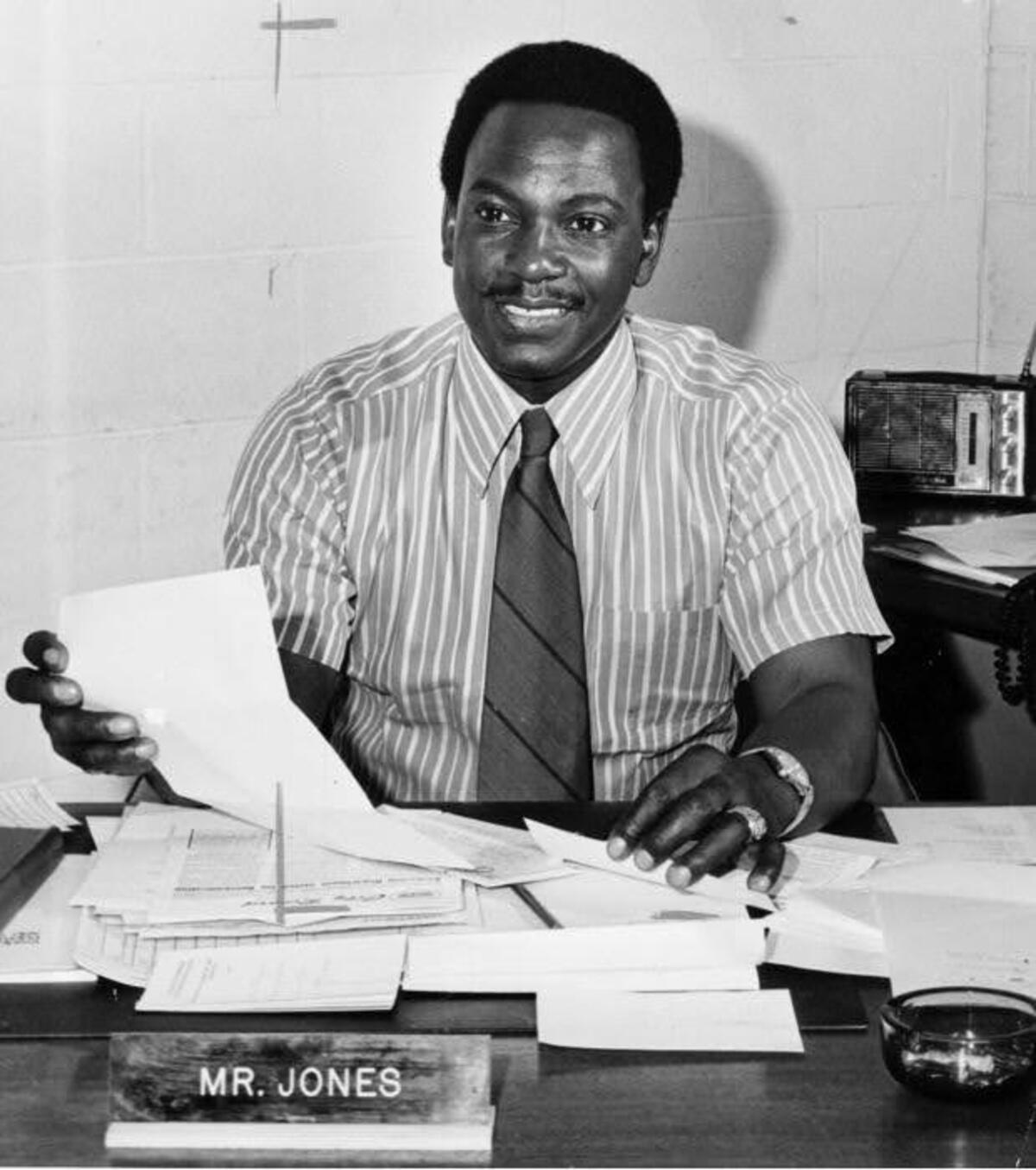

Clarence Jones

Jeep Jones Park, Roxbury

- You may or may not know that Jeep Jones Park in Roxbury is named after an important Boston figure: Clarence “Jeep” Jones. So, who is this important figure, you ask? Clarence Jones was a well known activist who was heavily involved within the Roxbury community. He played many roles and held many ‘first’ titles throughout his years in Boston. Through these roles, he paved a way for Black people all over to take on positions they’d never held before.

- Jones started his time as a crusader for equal racial representation in 1965 when he became the first Black Juvenile Probation Officer in Boston. He served as an officer until 1968, when he was elected to be Boston’s first Black Deputy Mayor, a position he would occupy until 1981. At the time he was elected Deputy Mayor, he was the highest ranking Black public official in Boston’s history. Jones also served as the first Black director of the city’s Youth Opportunity Task Force and the first Black chairman of the Boston Redevelopment Authority.

- He was beloved in the Roxbury community for the programs he led and was known as a role model. As a veteran, an activist, a public official, and a community leader, Clarence “Jeep” Jones was awarded an honorary doctorate in public service by Northeastern in 2005. He was also a part of the university’s Lower Roxbury Black History Project. He is remembered as a role model, mentor, leader, and advocate.

- Read more about Clarence Jones and the Jeep Jones Park.

Photos from Mass.gov

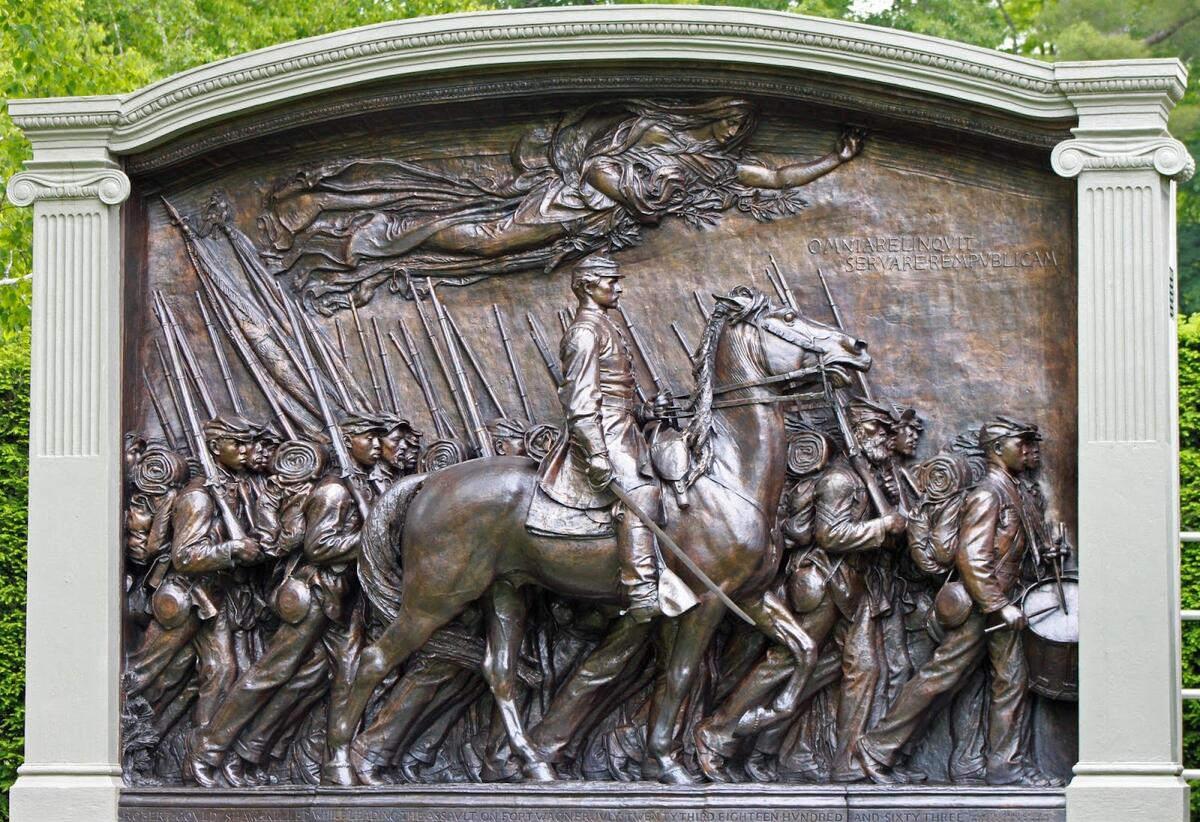

The 54th Massachusetts Regiment

Boston Common

- Directly across from the Massachusetts State House at 24 Beacon Street lies The Colonel Robert Gould Shaw and Massachusetts 54th Regiment Memorial at Boston Common. This memorial depicts and honors one of the first Black fighting units to serve in the American Civil War. The brave regiment fought at Fort Wagner and aided in changing the North’s negative public stance on the employment of Black soldiers. Their courage inspired the enlistment of more than 180,000 Black soldiers during the war.

- Commissioned in 1883 to commemorate the regiment and their valor, Augustus Saint-Gaudens was tasked with creating a memorial in the Boston Common. The sculpture took nearly 14 years to complete, and was dedicated in 1897. It has long-since been considered a masterpiece and is particularly significant for being the first monument to honor Black soldiers with individual faces. At the time, in group portraits, especially those of Black people, individuality was erased and group faces were nondescript or disfavored. Going against the grain, Saint-Gaudens modeled the soldiers after real people and emphasized humanity, individuality, and the deep respect the soldiers should be given throughout the piece.

- The monument continues to stand as a powerful symbol of the 54th Regiment's service and sacrifice. Many important national figures, such as Harriet Tubman and Colin Powell, have participated at events here and even today, the memorial continues to inspire people from all over.

- Read more about plans related to the memorial from the City of Boston website, and more about the memorial from alternate sources.

Photo from Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum

Photo from History.com

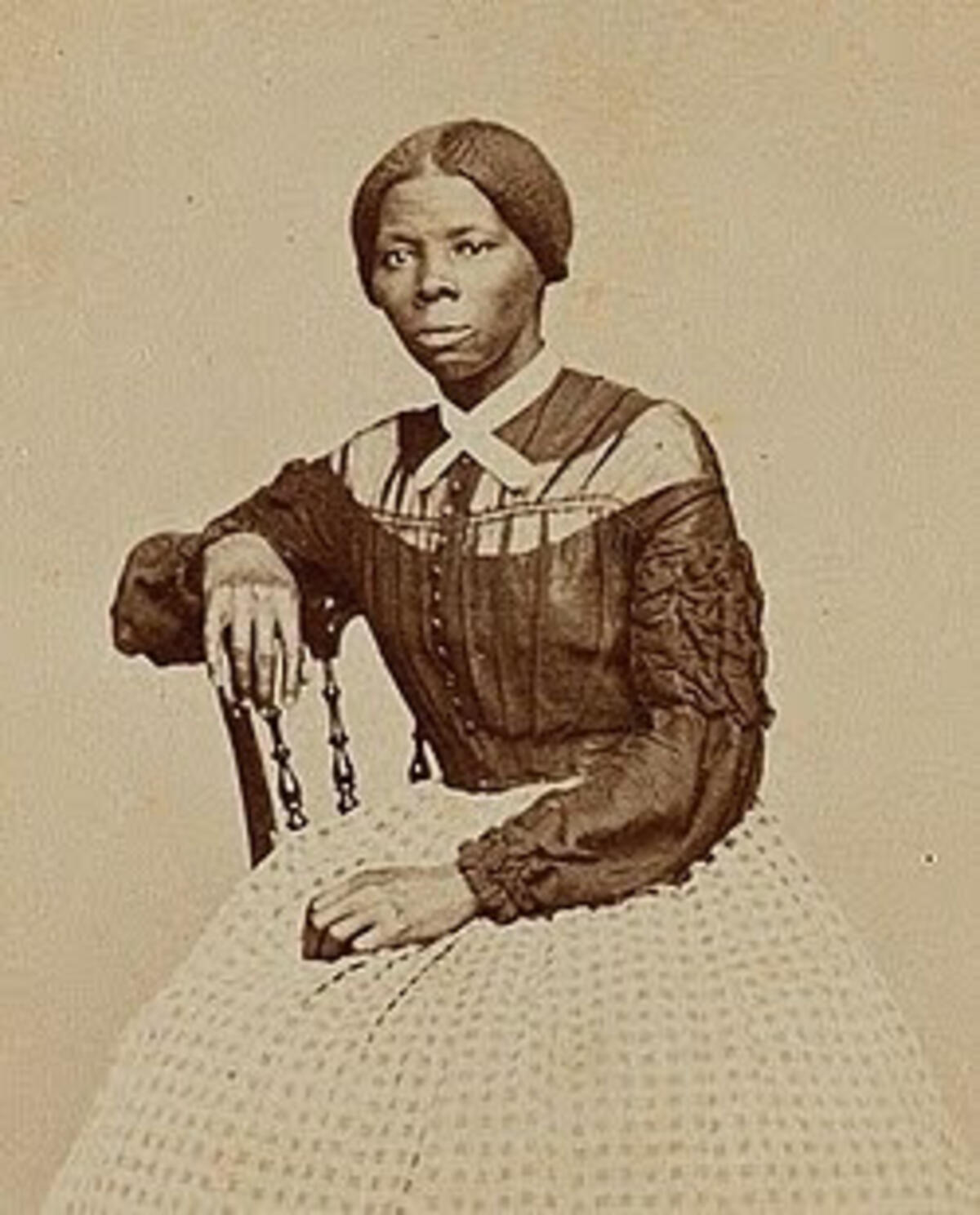

Harriet Tubman

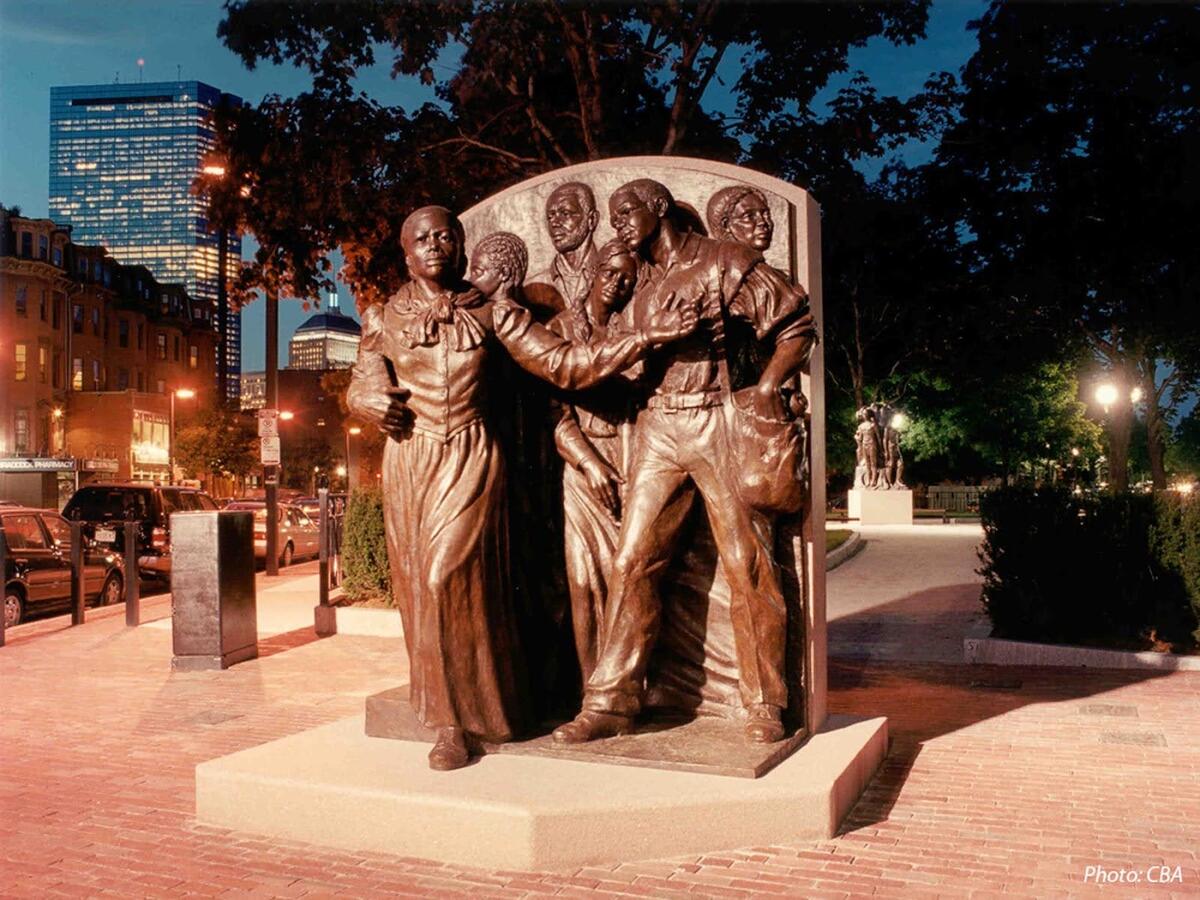

Harriet Tubman Square, South End

- Sitting just past West Newton Street and Columbus Avenue is Harriet Tubman Square (also called Harriet Tubman Park), a park honoring the incredible woman who saved approximately 70 people from slavery after escaping it herself. This square features a sculpture of Harriet Tubman leading people away from slavery. It was created by Fern Cunningham and named: “Step On Board,” serving as a powerful tribute to the abolitionist, civil war hero and civil rights activist. The sculpture is 10 feet tall and it was the first statue on city-owned property honoring a woman. Additionally another sculpture lies in the square, called: “Emancipation” by Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller, to honor Harriet Tubman. This sculpture displays a powerful representation of freed people stepping into a new world.

- Widely recognized as the leader of the underground railroad, which led escaped enslaved Black people from the South to freedom in the North and Canada, Harriet Tubman was an extraordinary person. She started her life in 1822 as an enslaved woman, growing up on a plantation in Maryland that was home to the Brodess family and what is believed to have been about 40 enslaved Black people. Tubman fled to the north where she found her freedom in 1849.

- After gaining her own, Tubman dedicated her life to finding freedom for other enslaved people, eventually leading at least 70 people to freedom in the North over what is believed to be around 13 trips up and down the underground railroad. In addition to freeing people from slavery, she also fought to end slavery overall and to improve the lives of both Black people and women of all races. From the moment she escaped, she risked her life time and time again to help others and fight for equal rights for all races and genders.

- Harriet Tubman continues to inspire people with her bravery and she will always be remembered and celebrated for her devotion to equality and justice for all.

- Read more about Harriet Tubman and Harriet Tubman Square (a.k.a. Harriet Tubman Park).

Photo from Boston Women’s Heritage Trail

Photo from britannica.com

Crispus Attucks

Boston Common

- In the Boston Common near Tremont Street and Avery Street lies The Boston Massacre Memorial, which is also called the Crispus Attucks Monument, made by Robert Kraus. The memorial portrays a standing bronze figure meant to signify the Spirit of the Revolution, inspired by Eugene Delacroix’s painting of Liberty Leading the People which was a symbol of the French Revolution. The figure holds a broken chain in one hand to symbolize freedom from oppressors and the American flag in the other. Beneath her right foot, she crushes the crown of the British monarchy and on the other side of her sits an eagle preparing to fly.

- This memorial was dedicated in 1888 in honor of Crispus Attucks, a man of African and Indigenous ancestry, along with the other victims of the Boston Massacre on March 5, 1770. The Boston Massacre was an instance of slaughter led by the British forces against the city of Boston that would eventually lead to the beginning of the Revolutionary War. The British referred to this event as the “Incident on King Street” and an “Unfortunate Disturbance.” In the foreground of the frieze lies Attucks, the first death in the massacre, the death that would bring about the American Revolution.

- Crispus Attucks was born into slavery but was able to become a free man, living as a sailor and skilled whaler. As the first person killed in a massacre that was followed by the Revolutionary War, Attucks' life became representative of resilience and the fight for freedom, justice, and equality.

- His legacy continues to uphold ideals of resistance and the need for pushback against oppression. Crispus Attucks is remembered as a hero of the Revolutionary War.

- Read more about Crispus Attucks from boston.gov and other resources, and The Boston Massacre Memorial (a.k.a. The Crispus Attucks Monument).

Photo from American History Central

Photo from Crispus Attucks Museum

Albert “Bootsie” Lewis

Hunt-Almont Park Tennis Courts, Mattapan

- Albert “Bootsie” Lewis is a Mattapan native. He has dedicated his life to enriching the Black communities in the Boston area. Not only was he an incredible tennis coach, but he also co-founded Sportsmen’s Tennis & Enrichment Center in Dorchester. This sports club was the first nonprofit indoor tennis club in the country built by and for the Black community. The efforts of Lewis and others pushed the sportsclub into a national spotlight, gaining it national recognition and winning it many awards. STEC continues to dismantle social and racial barriers through tennis and youth development.

- Tennis has a long, racially motivated history behind it. It has been systemically set against people of color, and especially Black people, for nearly its whole history. Although some progress has been made to make the sport more accessible and socially inclusive, it still has a long way to go.

- Lewis began his time as a tennis trailblazer during an especially challenging time when systemic exclusion and financial barriers kept many Black athletes from having access to tennis. With Sportsmen’s, Lewis and his peers created a space where Black youth could learn the sport and compete. His unrelenting dedication and leadership helped build a safe space in tennis for Black youth, and a place of education, community, and so much more.

- Lewis has earned many achievements throughout his career as a tennis coach and pioneer. A defining milestone came in 1970, when he became a USPTA-certified professional and began coaching full-time in service of his community. This milestone would lead him to his later ones, such as in 2000, he was appointed a lifetime board member at Sportsmen’s and later received the Commonwealth of Massachusetts Award honoring his decades of dedication. Most recently, in 2024, Lewis was inducted into the USTA New England Hall of Fame in recognition of his exceptional impact on tennis and youth development in Boston and beyond.

- On July 19, 2025, the City of Boston honored the beloved community leader and tennis pioneer Albert “Bootsie” Lewis with the official renaming of the tennis courts at Hunt-Almont Park in Mattapan. Come play tennis at his courts and celebrate the amazing man that he is!

Photo From USTA Website

Photo From the Dorchester Reporter